Most martial arts teach basic defences against a straight punch. In Karate it might be blocking, in Aikido it might be irimi and so on.

The fastest human punch on record travelled at 20 m/s. Many boxers can reach 14 m/s with a jab.

Let’s consider the worst-case scenario. In the case of a “sucker” punch travelling one meter at 20 m/s, you will have less than a tenth of a second to react. Neurologically speaking, you will be at the limits of your ability to perceive the punch coming, let alone decide to move.

There’s a comparable situation in baseball. When a pitcher throws a 100-mph fastball, the batter has to decide whether to swing or not the instant the pitcher releases the ball, before it even travels toward the plate.

So, how do boxers avoid fast jabs? (Often, they don’t!) It’s a combination of pattern recognition, preemptive movement and hard-wired reflexes developed in training.

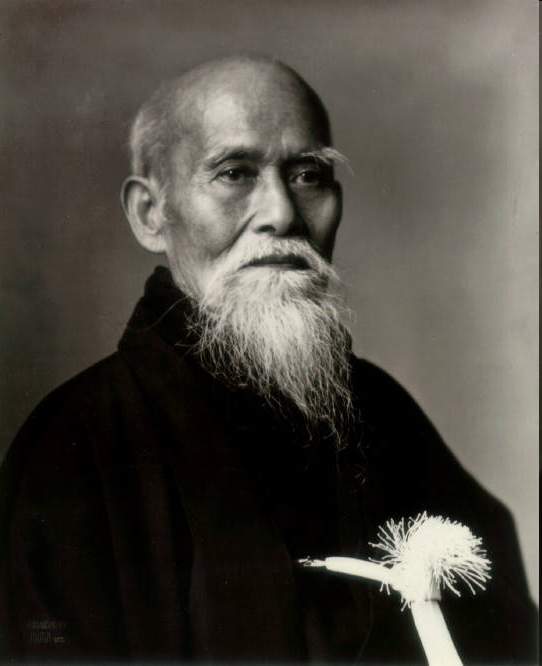

The great martial artists understood this well.

- Awareness: They had a sixth sense about a possible attacker’s intentions.

- Ma’ai: They had a profound understanding of distance, how close someone had to be to reach them.

- Timing: They understood timing, about “swinging the bat the instant the ball was released.”

- Intense training: They had built hard-wired responses to such situations, honed reflexes as natural as blinking an eye. Instant technique — no decisions required.

They say that O-sensei could dodge bullets.

If you’re interested in “realistic” practice, train intensely on the fundamentals, like awareness, ma’ai, timing and sabaki. Practicing complicated techniques is fun — but getting punched in the face is not.